HOTELS

www.vesnapavlovic.com

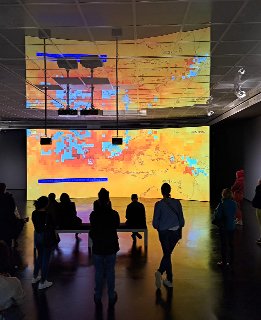

Hotels (2000-2002) are a series of color photographs of Yugoslav hotel interiors, representatives of the local 1960s socialist modern design. Empty and deserted, with a lingering atmosphere of past times, these spaces have become spectacles of anachronism. Those interiors, observed in the series as non-spaces, bring back the atmosphere of the “golden age” of Yugoslav socialism, the psychology of the times, and how it is shaped in constructed spaces. Small exhibitions of the Hotels images were staged in hotel rooms, brought back to its places of origin, being on view only to the hotel guests.

“Mixing deadpan observation and richly speculative imagination, Vesna Pavlović photographs the interiors of the once-grandiose hotels that were built during Yugoslavia’s “golden age” in the 1960s and ‘70s. Like many of her artistic contemporaries, Pavlović is less interested in analyzing the formal aspects of architecture than in evoking the collective psychology that shapes constructed spaces. With an ironic precision, she registers the colors and patterns of carpets, the textures of wall coverings, the fabrics that adorn curtained windows, the design of decorative objects, and the arrangement of room furnishings. Together, these details evoke the complex aspirations – sometimes laudable, sometimes laughable – that characterized a particular era of East European socialism.

In the past two years, Pavlović has photographed more than 20 hotels in different Serbian cities. She concentrates on structures erected at the high point of Yugoslav socialism, finding that they often bear traces of their use by the country’s former political elite. In style, these building are utterly distinct from the plush, ornate, massively intimidating Stalin-era hotels erected throughout Eastern Europe during the 1950s. What awakened Pavlović’s interest was her discovery of what she calls a “local socialist modernism” that distantly echoes the functionalist ethic of the Bauhaus in the 1920s or the School of Ulm in the 1960s. Despite their sometimes heavy-handed ceremonial touches, the spaces that Pavlović photographs seem designed less to be intimidating than slyly insinuating. Pavlovic practices a kind of photographic observation that seamlessly blends description and interpretation. For the patient viewer, her photographs hold cumulative lessons that illuminate much more than the architectural traces of the socialist epoch in Eastern Europe.”

Writer. Blogger. Traveler. Researcher. Electronic Music Lover.